I’m just back from the dentist’s office, where I had the usual one-sided conversation with Chris, the tech who cleans my teeth. It’s hard to be articulate with a sharp object probing your wide-open mouth, so my part of the dialogue pretty much consists of “unnh, unnh,” while Chris talks about her husband’s job and her kids’ achievements. But she tries to be polite and, as most people who have known me for any length of time tend to do, she asked how Frankie was.

I’m just back from the dentist’s office, where I had the usual one-sided conversation with Chris, the tech who cleans my teeth. It’s hard to be articulate with a sharp object probing your wide-open mouth, so my part of the dialogue pretty much consists of “unnh, unnh,” while Chris talks about her husband’s job and her kids’ achievements. But she tries to be polite and, as most people who have known me for any length of time tend to do, she asked how Frankie was.

I said, “He has doggie Alzheimer’s.” Not only is that quicker to say than Canine Cognitive Dysfunction — of particular use in this situation — but it’s far easier for people to comprehend.

It also has the benefit of being accurate.

Like most people, Chris laughed nervously and said,”I never heard that dogs could get that.” And then she asked how I knew he had it.

Excellent question — but not one that I could answer with sharp instruments in my mouth.

The Decision to Test for Cataracts

Last September, I took Frankie to see a veterinary ophthalmologist about his cataracts — in spite of vowing, long ago, not to subject him to surgery if they developed, as is common for dogs with diabetes. For one thing, the surgery is expensive. For another, I know that dogs generally adjust well to blindness.

But that was theoretical. The reality melted my resolve. Once I began noticing Frankie bumping into things and staring off into the middle distance, as though he could not see, I couldn’t bear the idea of not trying to help him — yes, even at age 14.

The Eye Exam

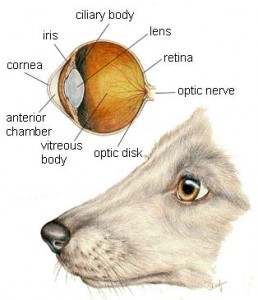

The young eye specialist I went to see was very nice and very gentle with Frankie, so I can’t say precisely why I had an uneasy feeling almost from the start of the eye exam; there was something about her body language as she went through the steps of looking at him with lights and finger tracking — pretty much the same as a human eye exam, except for not asking him to read an eye chart — that raised my anxiety levels.

After returning Frankie to my lap, she started out with the good news. Although he was largely blind in his left eye, she said, the right eye looked pretty good. She had gotten Frankie’s chart from my regular vet and praised me for keeping Frankie’s diabetes under such good control for so many years. She said his eyes were in comparatively good shape for any dog his age, and especially for one with long-term diabetes.

I adore my regular vet but he has told me repeatedly that there is no correlation between keeping Frankie’s blood sugar under control and avoiding cataracts. I was just lucky, he suggested. I thought differently. Ha — vindication!

The bad news, however, squelched any feelings of pride. The specialist believed that the problem wasn’t with Frankie’s eyes, but with his brain: He had enough vision to function normally but she thought the signals were getting scrambled, causing disorientation. These were signs, she said, of Canine Cognitive Dysfunction. I brushed off her explanation of what that was. I knew all too well.

I also knew in my gut that she was right — Frankie had other symptoms that I believed fit the profile — but I wasn’t quite ready for the diagnosis.

I grabbed at the only other possible cause the specialist offered for the eyesight issues: retinal atrophy. And so I spent another $500 getting Frankie’s retinas tested to determine if this progressive disease was causing the problems.

It wasn’t.

My reaction

It’s completely irrational, but my first reaction was to be embarrassed — both for me and for Frankie. The specialist said that his responses to stimuli around him in the kennel while he was waiting for the retinal test were abnormal — that he didn’t look around with curiosity at the other dogs or at the clinic staff. She took that as further confirmation of her CCD diagnosis. All I heard was that my smart terrier boy had failed an intelligence test! The shame.

And me? I’d written about CCD on this blog when Archie, the late dog of my BFF Clare, was diagnosed with it. What kind of journalist/dog expert was I?

The human kind who avoids painful situations, it turns out, and also someone who didn’t know that the symptoms of CCD aren’t uniform. But I’ll get to that another time.

We went through CCD with Lilac and it’s tough. I understand your feelings. For us, it was a battle of several years with no sleep at night, but she lived to be older than sixteen years old and we enjoyed our time with her. It taught me a lot of patience and a lot of compassion.

Happily, Frankie is sleeping through the night now, though he wasn’t at one point. And yes, patience and compassion are needed — in spades! I’ve been surprising myself. I’m glad you were able to enjoy your time with Lilac, in spite of the sleepless nights and the other associated difficulties.

It was still news you didn’t expect, and it took you off-guard. No shame in taking a few side steps to re-find your bearings to get used to a new situation, Edie. You always act in Frankie’s best interest, and you accept, wherever he might lead you. Kudos.

Thanks, Leo. Well, there would be no point in setting up a guilt free zone if I didn’t stray out of it now and then…

It’s heart wrenching and I understand your denial. How bumped into an alternate dimension it must have felt that Frankie now had what Archie had. The trials and labors of a dog mom can require more of us than we ever anticipated. All worth it, of course.

Yes — there’s that state of panic and then, eventually, acceptance. Unfortunately, unlike dogs, we humans contemplate the future and find it difficult to deal with, anticipating problems that may (or may not) come to pass.

It’s a tough diagnosis, for sure. I’m so sorry that this is part of your journey. When Lilly’s brain inflammation caused both physical and cognitive outcomes, I felt many of these same worries. I refer to it now as Lilly being “round” … compared to sharp / edgy girl of her youth.

Thanks, Rox. I know you understand… And I’m sure the sudden onset was tougher than my slower road of diagnosis. I like the idea of Frankie “being round” as opposed to edgy!

CCD is not a diagnosis that’s easy to accept. Denial would have been my first move. And, it’s not just the CCD, although that in itself is enough on which to spin out, but what is means. Aging and ultimately death. So many of my friends and family, including Frankie, have been diagnosed with end-of-life or nearing-end-of-life diseases. Many have already passed. I was far more philosophical about such inevitabilities in my youth when the horizon line seemed so far away. Not so much anymore. Now I just feel great tenderness and empathy for you and Frankie (who is probably handling this best of all), and for all of us inevitably bound to this existential predicament inherent in being alive.

You’re right, Deborah. It’s the whole complex of associations — and the fact that they don’t seem so far removed from my life anymore — that makes such a diagnosis difficult. I thank you for your tenderness and empathy. If I ever wonder why it is I started back pet blogging again, I’ll come back and read your very touching note.

It’s so true: Frankie doesn’t seem to be having problems handling things. It’s certainly not keeping him awake at night — or in the daytime — as it is me!

Coincidentally, an eye checkup precipitated Archie’s diagnosis. His corneas had clouded, and as his behavior became a bit vague–he had always been quite determined–I thought he had cataracts. And I really get that embarrassment/guilt factor: when the vet told me Archie had CCD, I felt that she–who had always fawned over Archie, and agreed he was a genius–was telling me that he wasn’t so wonderful or smart after all, or that I had somehow done something to cause his mental decline (did the decline start when he was mauled at the beach? I should have prevented the attack!). It didn’t help that she led me to believe that it was an unusual disease. Your story, along with those of your community tells me quite the opposite, and that’s reassuring in its way.

Ah, Clare, of course you would understand! I didn’t spin down into the “and it’s my fault” hole — the post was getting too long! — but boy do I get that part too (I shouldn’t have given Frankie his last dental; he seemed never to recover from the anesthesia…).

It’s NOT unusual! I’ll go into more details soon, but after age 12 a large percentage of dogs show at least one sign of CCD — and it progresses from there.

I’m so sorry about Frankie. I pet sat a delightful terrier mix, Shelley, that suffered from CCD. It was difficult to watch the changes, but I tried to focus on the things that still gave her pleasure, including walks and chicken and rice. I hated that no matter how gently I approached, most often I startled Shelley, who suffered from loss of sight and hearing. Good luck with your boy.

Thanks, Emmy. In some ways, Frankie is in good shape. He still initiates play (though he forgets mid-game — luckily, because he bumps into things while he chases his squeaky toy) and he rarely has accidents in the house. But like Shelley he can’t see, and although he can hear, he doesn’t always know where the sound is coming from. It’s tough…